You always remember where you were during one of history’s turning points. Three decades have now elapsed since Ayrton Senna met his tragic, shocking and still unfathomable end during the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix. Perched on a university housemate’s malodorous bag of hockey goalkeeping gear, I watched it unfold on a 14-inch TV. Viewing footage of Imola 1994 still summons to mind the fug of long-inhabited sports garb, like an incongruous and disconcerting reverse madeleine de Proust.

Back in those days the BBC did not deign to broadcast qualifying (Grandstand on 30 April featured horse racing, snooker, and the rugby league Challenge Cup final instead; BBC2 was showing a war movie). So viewers in the UK had been spared the sight of Roland Ratzenberger’s fatal accident, though it and Rubens Barrichello’s terrifying practice shunt were covered – with the Beeb’s usual discretion – in the pre-race package.

Hindsight affords a 20/20 perspective so it is easy now to catalogue the warning indicators which went unheeded as Formula 1’s circumstances aligned around disaster. Banning the so-called ‘driver aids’ ahead of that season had unforeseen consequences in the form of a grid packed with cars which were now dangerously unstable, since their aerodynamics had been conceived to take advantage of the stable platform afforded by active suspension. In his autobiography the late Max Mosley dismissed this as “the worst sort of post hoc analysis”. But then he would say that, wouldn’t he?

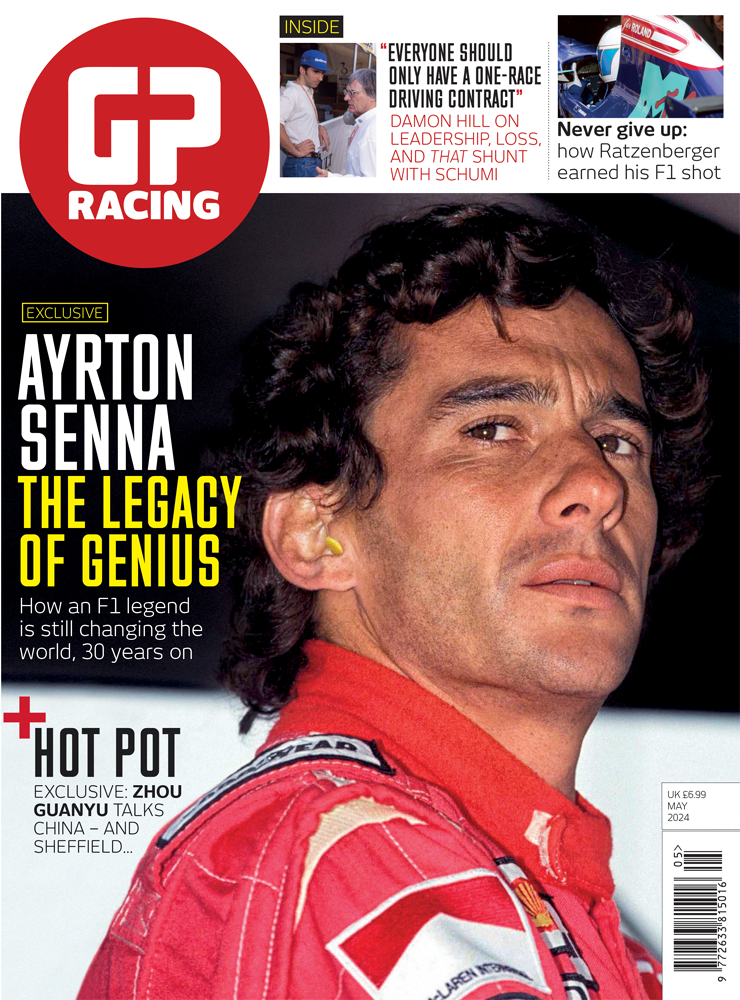

This month we mark the anniversary of that dreadful weekend with personal recollections of the people Formula 1 lost. Pat Symonds was Senna’s first race engineer in F1; Gerhard Kuntschik had known Ratzenberger since 1980, when the young Roland had accosted him for advice on how to get into motor racing. We also look at how the Senna family is continuing to work to realise Ayrton’s wish to create better life opportunities for young people in Brazil.

Besides being a phenomenal natural talent and a fiercely competitive individual, Senna was acutely aware of the fact that his journey to the pinnacle of motor racing had been eased by his family wealth. He wanted to give something back.

Ratzenberger was a late starter in motor racing and worked as a mechanic to pay his way through the junior categories. His family didn’t share his ambitions. But Senna did, and he respected the not-so-young man who had fought his way to the top – to the extent of packing an Austrian flag in his FW16’s cockpit to wave after the race.

F1 drivers may gripe and moan about their fellows in the heat of competition, but they know what makes each other tick.